American Barbecue: South Carolina

Barbecue keeps me a patriot. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I just saw online that in Britain they call putting something under the broiler barbecuing—don’t get me started—and people from lots of cultures, some Americans included, refer to backyard grilling as barbecuing.

That is not what I’m talking about; you can’t barbecue a hot dog, not really. When I say barbecue I refer to the culinary tradition, born in the American south in which meat is cooked slowly—often very slowly—with smoke or indirect heat.

Little Pigs Barbecue: just the sides.

The origin of barbecue is obscure and contested, interweaving the culinary traditions of Native Americans, African slaves, Caribbean islanders, Mexicans, the colonial powers, and Southern whites. You don’t get much more American than that. And there is so much that's true of barbecue that is also true of America itself: barbecue is at once part of our shared national identity and at the same time fiercely local, regional, even protectionist; like America, barbecue is oftenperceived as rural and unsophisticated but is in practice deeply nuanced and complex, taking an enormous amount of expertise, talent, and often multi-generational dedication to do right; and like America barbecue's unique poetry comes from deep pain and suffering, for most of its history barbecue represented a rare celebration in a life defined by hardship—nothing in this country involving African Americans and Native Americans is going to have a very happy history.

So all "true barbecue" must be meat cooked "low and slow", at low heat and for a long time, but after that all bets are off.

When it comes to barbecue there are many, many regional differences: from the well-known Kansas City and Memphis styles, to the more obscure. Every hear of Alabama white sauce? Or Kentucky barbecue mutton?

My personal barbecue pilgrimage started in South Carolina.

There is no true "Carolina style" barbecue, the situation is much too complex for that. The Carolinas are divided into a whole slew of micro-regions, each with their own local barbecue tradition; the one thing they all have in common is pork.

In the Piedmont area of North Carolina the slow smoked pork is served with a tangy, ketchup-based red sauce. In Eastern North Carolina whole hog barbecue is the way to go: the pig is slow cooked whole before being picked apart and served simply with a splash of vinegar.

South Carolina embraces both styles of sauce, and brings one of their own to the table: a sweet, yellow, mustard based sauce that was introduced by the many German immigrants who settled in the state over the last 200 years. Because of their relative sauce-open-mindedness South Carolina is the perfect place to get an introduction to the region's diverse barbecuing traditions and perhaps the best introduction of all is at Little Pigs Barbecue in Columbus, the South Carolina state capital.

Little Pigs Barbecue: pulled pork with vinegar, pulled pork with mustard, and a chunk of sausage.

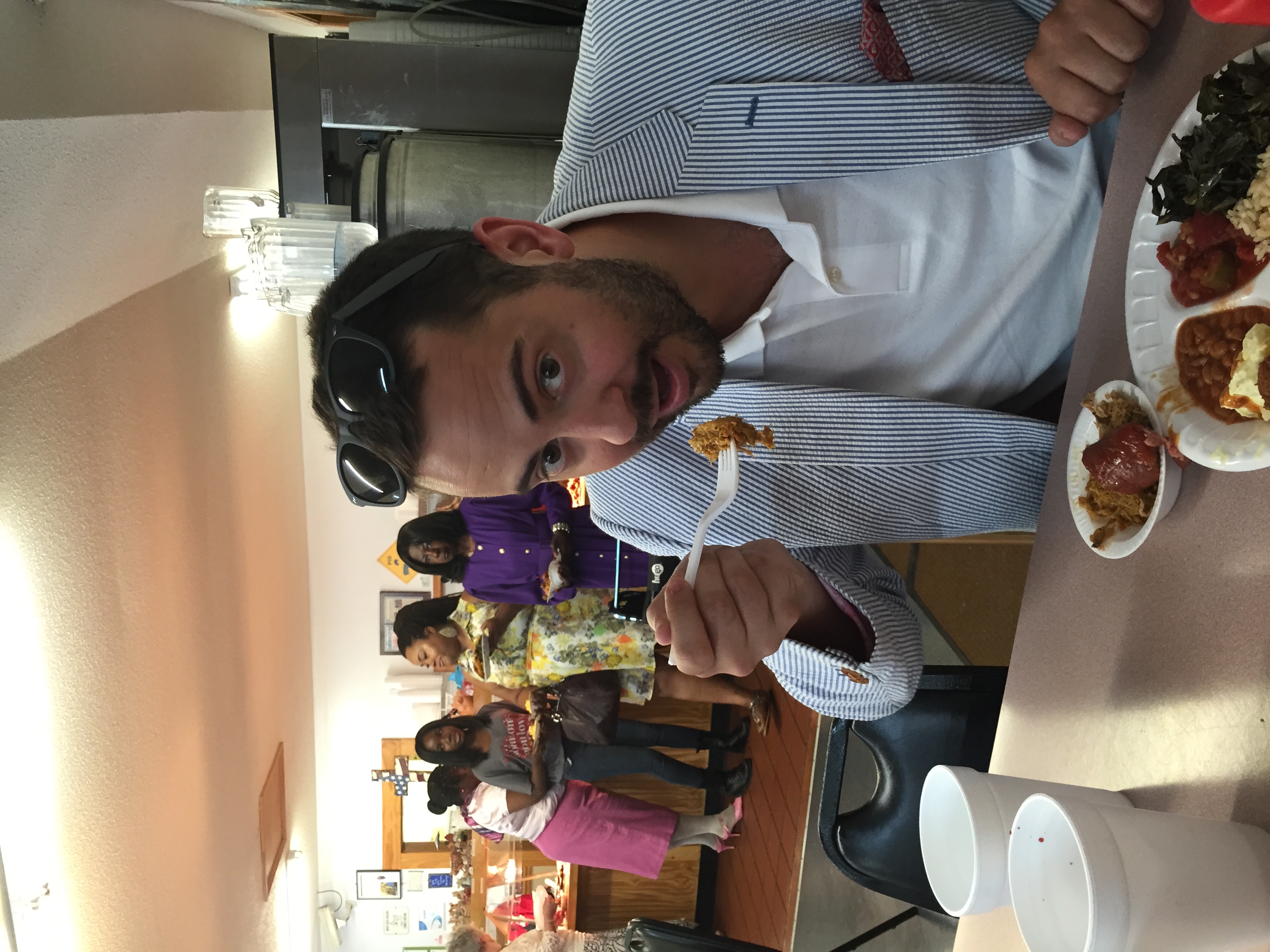

It was Sunday afternoon when we pulled off the freeway and found the Little Pigs sign; the dusty parking lot was filling up fast. Inside it seemed like the whole neighborhood had decided to stop in after church. Little Pigs was full to bursting with families in their Sunday best, little kids in clip on ties weaving in and out of the buffet line, old folks in their wheelchairs waiting for their grandchildren or great grandchildren to bring them styrofoam plates piled with steaming chopped pork.

The restaurant consists of one large two-sided buffet, and a small island in the middle of the room for plastic forks, napkins, and desserts. Not only did the buffet boast all of the traditional Southern fixins: baked beans, mac n’ cheese, fried okra, hush puppies, and fried chicken, there were also some deep South folk-gems I had never seen before like tomato pie and a pile of dark chocolate-brown fried livers the size of babies’ fists.

Fried everything.

Then there was, in glorious profusion, the barbecue.

Little Pigs had it all, and so did I.

Everything was good but the pulled pork in vinegar was the star of the afternoon. The lightness off the vinegar let the pig sing out loud, deeply porky, its fatty sweetness cut just enough by the sauce. The flavor was remarkably similar to the best Filipino fried pork and vinegar dishes like lichen koala and crispy pata.

That's mustard sauce bbq on the back left, and vinegar to the right.

The livers were also a surprise. They were excellent, not too fried and not too livery but rich, with only the faintest bite of iron. I did enjoy the pork in mustard sauce, the region’s signature style, but the sweet mustard for the most part over-powered the flavor of the pork, though it would be excellent on a sandwich no doubt—it’s worth noting that I was in the minority here, everyone else at my table preferred the mustard sauced pork.

Pre black out

We also had to try dessert which at Little Pigs consisted of a series of vats next to a tray of sliced dill pickles. Inside the vats was a delicious yellow mush (banana pie) and also a tasty brown mush (Chocolate delight). They were both good in that way instant pudding mixed with peanut butter is good (read very).

Look at that liver!!

The South it seems is not big on recycling, so after many trips to the trash can to throw away the sticky heap of styrofoam plates, bowls, and plastic cutlery, and waddling towards the door, I wondered idly—not hungrily mind you—that the only kind of Carolina barbecue not present was whole-hog style. "Probably a good thing," I mused, burping and picking my teeth, "I'd have to try it, and one more bite of pork might push me over the edge."

Well wouldn't you know, coming around the back side of the dessert island, my mother pointed out a whole massive haunch of pig, crisp and shiny under heat lamps next to a greasy pair metal tongs.

Quivering, I peeled off a shard of skin, picked apart a small pile of fatty pale meat, and retook my seat.

Somehow my stomach made room, and lord was I glad it did. The tiny stack of skin and meat was smoky and tasted intensely of swine in the funkiest, farmiest most fantastic way. It was delicious, and the deep, gurgling nap I slipped into as soon as I got back in the truck was too.